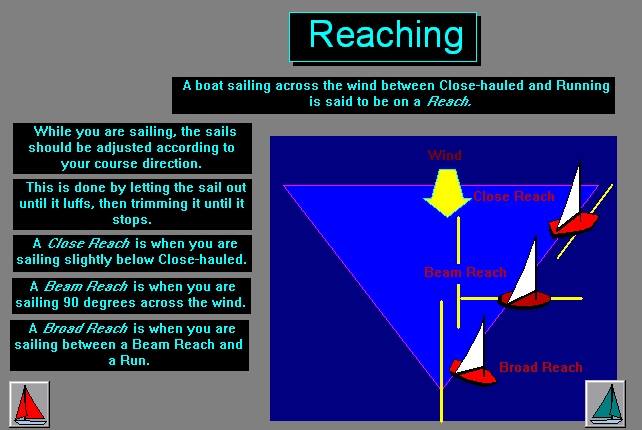

Reaching: A Point of Sail Sailing Term

Reaching: When a boat is sailing across the wind between close hauled and running. Reaching is a point of sail. Here is an infographic for you to share, like and print out. Happy Sails!_/)

The Disadvantages and Sailing Terms

Disadvantages— In serious wind and seas, a monohull sailor can, if absolutely exhausted and no longer able to steer, strike all sail, lock all hatches, and go below to wait it out and hope for the best. A well-found boat will most likely allow this. The boat will roll around like a cork, and even if it rolls 360 degrees it should be ok, as long as the mast doesn’t break off and put a hole in the boat. A Multihull in huge seas, however, must always have a helmsman, or some other way to keep the boat pointed into the waves. Without this, the boat will end up in the wave troughs, with the waves beam on; this is an invitation to capsize. Knowing this, the ocean going sailor should be prepared with a parachute sea anchor and with attachment points for it on the boat that are absolutely bombproof. Properly deployed, a parachute anchor will allow a multihull to ride out a hurricane in near comfort, as it keeps the bows pointed into the wind and waves and with several hundred feet of line led out to the sea anchor, there is no jerking or lunging on the line. Once the sea anchor is properly set, the crew can go below and safely wait out the storm. This assumes that there are no dangers, such as a landmass or reef systems, lying in wait downwind. Plenty of sea room is needed for these manuevers.

Marinas— Finding space in a marina for a multihull is not nearly as easy as it is for a monohull. They require either an end space or a double berth, which will likely cost more than a single.

Weight constraints — Since a multihull sits on the water instead of in it, unlike a keel boat, the payload, or weight carrying capacity of the boat, can not safely be exceeded. A catamaran, with essentially two full boats in the water, can carry more weight than a trimaran of the same length, which consists of one full hull and two floats. A 35 foot monohull can carry much more weight in stores and equipment than a 35 foot trimaran, and this is a consideration when provisioning a boat for cruising. The cruiser in a small multihull may find himself reprovisioning along the way more often than the cruiser in a small monohull.

Trailerability— Large multihulls cannot be shipped over the road, due to their wide beam. Only some of the smaller, folding designs will allow trailering.

Haulouts also can be more complicated for multihulls. There are yards that have travelifts wide enough for them, or cranes to lift them, or railways to pull them out of the water on tracks, but these yards are fewer and farther between than those that can’t handle the extra wide beam.

Conclusions — It seems that outside of a couple of minor inconveniences, a multihull is the only boat that makes any sense. If this is the case, why doesn’t everyone have one? There are a couple of reasons. One is the unfortunate reputation they earned early on in their evolution. The other is the expense involved in achieving ownership of a quality cat or tri. These boats are expensive to build, whether as one offs or as production models. With a trimaran, 3 hulls (amas) and crossarms (akas) to connect them all together are needed. For production this requires expensive tooling up for a company to invest in even before they ever get a boat on line. There are also a lot more materials needed to build two or three hulls than are needed for the one finished hull of a keel boat.

Other than a production model the buyer has the option of having one custom built by a reputable yard or of building it himself. Neither of these options is cheap, fast, or easy.

There are used multihulls on the market, and there are a lot of good ones out there. There are also a lot of not so good ones. It’s critical to hire an experienced multihull surveyor to be assured that the boat was built and maintained properly and is sound.

Sailing Terms

Amas-The outboard hulls of a trimaran.

Ballast-A weight at the bottom of a boat to keep it stable. Ballasts can be placed inside the hull of the boat or externally in a keel.

Beam– The widest part of a boat.

Draft– The depth of a boat, measured from the deepest point to the waterline. The water must be at least this depth, or the boat will run aground.

Catamaran-A twin-hulled boat. Catamaran sailboats are known for their ability to plane and are faster than single-hulled boats in some conditions.

Hatch-A sliding or hinged opening in the deck, providing access to the cabin or space below.

Heel-When a boat tilts away from the wind, caused by wind blowing on the sails and pulling the top of the mast over. Some heel is normal when under sail.

Monohull-A boat that has only one hull, as opposed to multihull boats such as catamarans or trimarans. Multihull-Any boat with more than one hull, such as a catamaran or trimaran.

Payload– Weight carrying capacity of the boat.

Trimaran-A boat with a center hull and two smaller outer hulls.

History -The catamaran is one of the oldest types of craft known. The word Catamaran has its origin in Malayan language — Catu (to tie) and Maran ( log). Early Polynesians would lash two large canoes together and sail a whole village’s worth people from one village to another, which usually meant sailing from one island to another. These people considered the stability of a two hulled vessel to be safer than that of just one hull. Until two centuries ago Polynesia was totally isolated from the rest of the civilized world, which was developing boats along what we now think of as more traditional lines – single-hulled keel boats, or monohulls.

In the 1780s Captain Cook reported seeing beautiful boats of up to 120 feet long which were built of painstakingly painted and polished wood. Exposure to the outside world brought European diseases to these people, who had no immunities to them. The populations and societies were ravaged and these beautiful vessels rotted away. Outside of some native activity in the Hawaiian islands the catamaran design disappeared.

Then, in the late 1870s, Nathaniel Herreshoff designed and built the 25 foot catamaran Amaryllis. In 1876 he entered it in the New York Yacht Club’s Centennial Regatta and easily beat every other boat in the fleet. That this upstart radical “new” design should win so handily was deemed unacceptable, and catamarans were barred from racing. This decision stopped the further development of multihulls cold. Mr. Herreshoff and his son, L. Francis, continued to design and build them for themselves, adding centerboards to each hull for better maneuverability, but their designs never gained acceptance.

1952 — in England, the Prout brothers designed a U shaped hull, instead of the V shape that had preceded it, and they included centerboards. Now the boats would actually tack. They became popular in Europe because of their speed and comfort, and the long slow process of design evolution took a step forward. By the late 50’s there were quite a few sailors experimenting with new designs and building materials. With the advent of fiberglass, resins, and marine plywood these boats could be built light and strong. In the 1960’s Rudy Choy of Hawaii was designing and building race winning, ocean capable catamarans which are still viable today.

During the 1960’s and 1970’s an American designer named Arthur Piver was singularly responsable for the building of hundreds of trimarans in the backyards of would-be sailors. Unfortunately, some of his claims were not realistic- he maintained that anyone without carpentry or sailing experience could quickly and cheaply build one of his “non-capsizable” designs and sail around the world. There were so many of his boats under construction at one time that there was no way he could even attempt to ensure that the builders were using proper construction techniques, or even sticking to his plans. This resulted in builders making major and often unsafe modifications to his designs, and in many boats being built poorly and with inferior materials. There are still many old Pivers out sailing that are safe and comfortable, but there are countless others that rotted away, capsized, or broke up at sea due to shoddy construction. Piver himself disappeared at sea on a boat of his own design, albeit one that he did not build himself. All of this did nothing to help the reputation of multihulls, a legacy that unfortunately exists in the minds of many today.

Jim Brown, a protege of Piver, started designing his own trimarans, called Searunners. He designed them with a wider beam for a safer, more stable platform, along with other modifications. Soon Norm Cross, Lock Crowther, John Marples, and countless designers from all over the world were building on the lessons that could be learned from previous designs, both with trimarans and catamarans. These designers realized the need for detailed, precise plans, and for the designer to be involved with the builder from day one of construction in order to help to create a safe, fast, comfortable vessel.

The racing world is where multihulls have had a real chance to show the world their performance potential . In the 1976 OSTAR Mike Birch came in second place on the Third Turtle, Dick Newick’s VAL design 31 foot trimaran. The first place winner that year was Eric Taberly on his 71 foot monohull. This was the last year in which a monohull won this race. Dick Newick’s designs also captured the attention of Phil Weld, who won the 1980 OSTAR in the Newick trimaran, Moxie.

The high profile of racing, the money that racing has brought into their development and improvement, as well as the evolution of new, lightweight synthetic building materials have all contributed to the high quality of multihull craft that is being built today. They have gained worldwide acceptance.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of multihulls?

Advantages.

Stability — It’s almost impossible to sink a properly built multihull, short of blowing it up or burning it down. A common misconception is that trimarans and catamarans are easily capsized. This is not true of cruising multis — they are stiff and stable and usually need a very rare and extraordinary set of circumstances before they’ll go over. It is true that once they go over they stay over, but they will not sink, even when inverted. The crew of a capsized multi still has the mother ship and the supplies aboard to sustain life for however long it takes for a rescue. This is in contrast to a monohull, which if holed or capsized with hatches open will very quickly sink, leaving its inhabitants swimming or in a life raft. The likelihood that a modern cruising multihulls will capsize is about the same as the likelihood that a monohull will sink.

Speed – Almost without exception, a modern multi will be substantially faster than a monohull of comparable length. Speed is not only fun, it’s an under appreciated safety feature. On a sailing passage, the longer a boat is exposed to the sea and the vagaries of weather, the better are the chances that it will meet with dangerous conditions. A North Atlantic crossing that takes under 10 days is likely to be safer than one that takes 3 weeks. A lot of weather can happen in three weeks, or a crew member can become dangerously sick and need medical attention fast. It’s good to be able to step on the gas and get there.

Jibing — These boats are so beamy that in a downwind situation the preventer can be secured far outboard, giving the main a lead that results in a nice wide, flat sail area and absolute control over the boom. Since multihulls move at such high speeds downwind, there is less wind pressure actually behind the sail, making it easy to control it during the entire manuever. The boat continues to sail flat and steering is easy. Jibing a multihull is a very smooth operation, and puts much less stress and strain on both equipment and crew than it does with a monohull in the same situation. In a jibe a keel boat will tend to roll and try to round up into the wind as the mainsail fills on the new tack, making steering tricky.

Comfort – It’s nice to be comfortable. After spending time on a modern multihull few people would argue that they are not considerably more comfortable than a keel boat. With their wide stable platforms catamarans don’t heel at all, trimarans very little, and most people find their motion to be easier than that of single hulled boats. Comfort is also another very important safety feature. On a stable, smoothly moving boat it’s easier to prepare and eat regular meals, and crew members can sleep without having to tie themselves in. A well rested, well fed crew is a much clearer minded, safer and happier one than a seasick, exhausted, poorly fed one.

Deck Space — on a boat where 24 feet of beam is common, there’s plenty of room to walk around. Dingy storage is not a problem.

Shallow Draft –Most multihulls have a very shallow draft — 2-4 feet. What a luxury to be able to manuever through a crowded anchorage and move up front into only 3 or 4 feet of water and drop anchor. In water this shallow it’s easy to see how well set your anchors are, or to hand set them if necessary. So what if all those big heavy boats behind you drag anchor? You’re upwind from them all, and are safe from being crashed into by drifting, dragging boats. Many beautiful, private anchorages are out of reach of deep draft boats, but are perfect for shallow draft vessels.

Run aground? No problem. The boat will sit level and undamaged. Just wait for a rising tide, if you can, or perhaps you can jump in and push the boat off. ( Be careful if you do this — wear shoes, and be sure that you can get back on board). You may also be able to walk out to deeper water and hand set an anchor that can then be used to kedge the boat off.

Here his a short animation on how to rescue crew that fell over board. This method involves jibing which is turning the boat around with the wind behind you. Only to be practiced in light winds as one can capsize easily!

Most one man-overboard drills usually consist of throwing over a cushion and returningto pick it up by the strap. A good sized fireplace log is a better way to do the practice because it is much more awkward to get aboard.

There are four important steps to retrieving a person who has gone overboard. The first is to return withoutdelay to a position near the victim. The second is to maneuver your boat close enough so you connect him or her to the boat. The third is to get the person aboard, and the fourth is to see that they are ok.

The moment someone goes over the side, a boat cushion or life preserver should be tossed to him/her.

Make sure to keep him/her in sight, and as the distance widens, it is increasingly important to maintain visual contact.Even when you are alone on the boat, keeping the victim in sight is second only to getting the boat back to him.Everything becomes more practical as you get in closer proximity to the person in the water.

Here are three methods of rescue. Please refer to our Quick Sailing Tips for animations of the 3 methods!

Method One…This method involves jibing to rescue the person over board. Only do this in light winds to avoid capsizing. Remember to stay in constant communication with the victim. 1.When a person falls overboard, immediately yell “Crew Overboard!” 2.Next, throw a flotation device toward the victim and keep a close eye on them.3.Jibe the boat.4.Now quickly head up to a close-hauled course. 5.Retrieve the person on the windward side of the boat. Let the mainsail out to stop.

Method Two… If the wind is too strong to jibe the boat, then tacking in a figure eight is a good way to go. Remember to stay in constant communication with the victim. 1.When a person falls overboard, immediately yell “Crew Overboard!” 2.Head on a broad reach for about 15 to 20 seconds. Keep your eyes on the victim.3. Then come about and head up.4.Go beyond the victim and come about again, proceeding on a broad reach. 5.Head up to the leeward side of the person and let the mainsail out.

Method Three…The Quick Stop maneuver is a new, widely recommended method that calls for the boat to go head-to-wind as soon as a person goes in the water. The jib is backed to further reduce speed while the continues turning until the wind is abaft the beam. The course is stabilized on a beam- to broad-reach for two or three boatlengths, then altered to nearly dead downwind.

If the wind is light, you can tack immediately after the person falls overboard and leave the jib cleated. Remember to stay in constant communication with the victim.1. First, immediately yell “Person Overboard!” and toss them a flotation device.2. Keeping an eye on the victim, immediately come about and backwind the jib by leaving it cleated. 3. Let the mainsail out so that it luffs and drifts towards the victim.4.Let the mainsail all the way out and uncleat the jib.

All these methods are good and each will benefit from practice. Most practice sessions are held in calm water onclear days, which is rarely the condition in which a man-overboard emergency will occur, so think about handlingthe situation in a storm, or at night, or in fog. The wise sailor reviews his plans for handling man-overboardscenarios every time he goes aboard a boat. He applies his plan to the conditions prevailing whenever he goeson deck. When a crewmember goes in the water there should be no delay in starting the best retrieval method.

Many safety authorities believe that the victim should be picked up on the windward side, but I believe that with a sailboat the leeward side is likely to be both lower and more sheltered, with the boom readily available as a mounting for the hoisting block. As the boat drifts to leeward it will drift away from a victim who is to weather, but will remain close to the victim to leeward. Watch out, though, to make sure that the boat bouncing in a seaway does not slam down on top of the swimmer.

Resist the temptation to have someone go in the water to help the victim – you may lose two people. If the person in the water is unable to help himself you then may have to send a spare person into the water to help. In this case make surethere is a line securely attaching the boat and the would-be rescuer. Plan ahead how you are going to get this person back aboard.

Of course the more you know about how your boat behaves under differing circumstances, the better will be your performance in any emergency. Picking up a mooring under sail, particularly in winds over 30 knots,teaches you a lot that you can use to save a friend’s life. At all times handle your sails at racing speed.Whenever you can, practice and think about what you are going to do in a man-overboard situation. The seconds yousave may be important in an emergency.

Best to you, Sailor Cull _/)_

In every sailor’s life lurks the inevitability of an eventual grounding. If you’re a sailor and you haven’t yet run aground, chances are very good that one day you will.

What to do When Running Aground

DON’T PANIC — doing the wrong thing can put you on harder.

Now that you’re on the bottom, take a minute to evaluate the situation. Check the bilge to be sure that you haven’t holed the boat and aren’t taking on water. What is the nature of the bottom? If it’s soft sand or grass, chances are good that the boat is undamaged, and that if you need to motor or kedge off you won’t grind a hole in the boat.Your objective is to get safely into deeper water.

Motoring off — If you have a motor or engine your first inclination will be to start it up and try to back out. This may work, but be careful. In sandy or muddy bottoms you are likely to suck sand up into the cooling system and render the motor useless. A powerful engine in shallow water can actually push sand from the stern to under the keel, making the situation worse. If you’re on rocks and you reverse hard, you may drag the hull along the rocks and damage or even hole the boat.

Set out an anchor. One of the first things to do is to set out an anchor to keep your boat from being pushed even farther onto the shoal. If you have a dingy you can use it to carry out an anchor. If you don’t have a dingy, and if conditions are calm, maybe someone wearing buoyant flotation gear can swim an anchor out. Be aware that this is not an easy task and a person can become totally exhausted very quickly. If your boat is a small one, your anchor is also probably small enough and light enough for you to be able to throw it far enough for it to work, but be careful if you do this. You don’t want to go overboard with it. Keep as much tension on the anchor line as you can. This alone may help free you up, especially if you have a rising tide, or if passing boats create enough of a wake to raise you up momentarily.

What is the state of the tide? If you’ve gone aground on a rising tide, you may just be able to wait a couple of hours until it rises enough to refloat the boat. If you’ve gone aground on a falling tide, however, you need to get into deeper water fast, or you may be stuck where you are for an entire tide change. If this happens, and if the boat is likely to end up lying on its side, close up hatches and companionways to keep it from flooding. If you’d be better off lying on one side than on the other, try to kedge off an anchor from what you want to be the low side. You may also be able to control which side ends up high by shifting crew and gear weight. Where is the deeper water? It may seem obvious that deeper water lies behind you, but it might be even deeper beside you. Of course it’s not directly in front of you — if it were, you wouldn’t have run aground in the first place. To find where the deeper water is, you have some options. If you have a lead line you can lower it off the boat from all sides to get a measurement of the depth. You can make a lead line by taking a light line and attaching a weight to the end. You could also very quickly put a boat hook or an oar in the water.

How do you get there? If you have a centerboard, raise it. This will decrease the draft, possibly enough to free the boat. Can you sail off? If you were sailing down wind when you ran aground, harden up and try to go to windward. If you were sailing close hauled, tack immediately and move crew weight to leeward. If sailing off on a reach or downwind would put you into deeper water, ease the sails and fall off toward the deeper water. Move crew weight around to heel the boat in the direction which is most likely to help it to slide off – this alone may reduce the boat’s draft enough to free her up. If this doesn’t work, drop sails, as the wind on the sails will continue to push you harder onto the shallow water. Furl them out of the way. On deck they will become a slippery liability.

Kedging off — Once you’ve set an anchor in deeper water, you may be able to winch it in and pull the boat off that way. Again, moving crew weight around may help immeasurably. It may help to rock the boat by shifting crew weight back and forth as you winch in on the anchor.

Use a halyard — If you know that heeling the boat in one direction will help, hand a halyard to someone in a dingy who can then carefully motor off the boat’s beam and pull it over farther. If you don’t have a dingy, a crew member can grab a halyard and swing out over the beam of the boat to try to increase heel.

Get off and push – This technique is obviously only safe and effective in very shallow water, and thus will only work with a very shallow draft boat, such as a day sailor or a multihull. Before getting in the water, be sure to put shoes on. Make sure that the boat won’t sail off without you, and that you have a way to get back onto the boat.

Accept tow? As a last resort, if all other options have failed. This may require a VHF call to a towing company. Be careful — a big powerful powerboat may be able to pull with more force than the boat’s equipment can handle–the boat’s hull can be damaged. The boat must have a cleat strong enough to take the strain of a tow, which may be considerable. If there is no cleat strong enough, consider tying off to the base of the mast. If the mast is stepped through the deck it will take the strain, if it’s stepped on deck it may not. The line used as tow line also must be strong enough to take the strain of towing — if it breaks under the strain of the pull of a tow boat, it will become a lethal weapon.

When you may not want to refloat the boat — if you have a hole in the bottom you may be better off right where you are, at least until you’ve been able to carry out enough of an emergency repair to keep the boat from sinking.

Sailing Terms

After bow spring line– A mooring line fixed to the bow of the boat and leading aft where it is attached to the dock. This prevents the boat from moving forward in its berth. Its opposite, the forward quarter spring line, is used to keep the boat from moving aft in its berthBilge– The lowest part of the interior hull below the waterline.Centerboard – a fin shaped, often removable, board that extends from the bottom of the boat as a keel.Cleat– a device used tosecure lines made of metal or wood.Halyard – a line used to hoist sails.Keel – centerline of a boat running fore and aft; the timber at the very bottom of the hull to which frames are attached.Kedge -To use an anchor to move a boat by hauling on the anchor rode; a basic anchor type.Rode – The anchor line and/or chain.

MOB Man Overboard! or Crew Overboard or Person Overboard Whatever your preference! Here are 3 short animations on how to rescue crew that fell over board.

Method 1: This method involves jibing which is turning the boat around with the wind behind you. Only to be practiced in light winds as one can capsize easily!

Crew overboard 2nd method! This involves a crew member falling overboard with the sailboat coming about, heading up, coming about and heading down, picking up the victim on the leeward side.

Crew Overboard 3rd Maneuver! Known as the “Quick Stop”, The “Quick Stop” method is taught at the United States Naval Academy, and is the maneuver recommended by US Sailing.

Approaching a Mooring in a Sailboat – Sailing Tip

Here is a printable infographic on how to land a sailboat at a mooring. Always be mindful of the wind!

Some way to tell which way the wind is blowing is to observe flags and birds always face the wind.

How to land a sailboat at a mooring

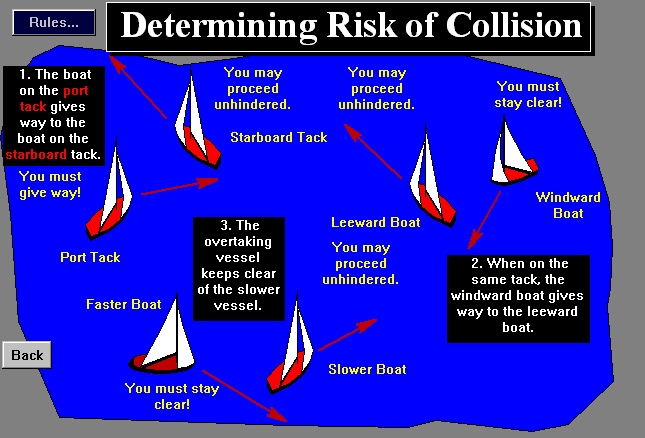

Here is a printable infographic on the risk of collision rules.

Typically, when two sailboats encounter on the high sea, there are three nautical rules to follow:

1. The boat on the port tack gives way to the boat on the starboard tack. 2. When on the same tack, the windward boat gives way to the leeward boat. 3. The overtaking vessel keeps clear of the slower vessel.

To learn more about the rules of the road, Download a Free! “Rules of the Road” article with graphics.

Crazy, courageous, or something else, teens are casting off on a global sailing adventure. With the circumstance of Abby Sunderland, teen world circumnavigation is getting lots of press. But this is not something new with the likes of Robin Lee Graham, who as a teenager set out to sail around the world alone, of 1965, and Tania Aebi who embarked on the same venture at 18 years of age in May, 1985. Both achieved their goals and have excellent books (“Dove”, Graham), (“Maiden Voyage”, Abei) of their story.

Crazy, courageous, or something else, teens are casting off on a global sailing adventure. With the circumstance of Abby Sunderland, teen world circumnavigation is getting lots of press. But this is not something new with the likes of Robin Lee Graham, who as a teenager set out to sail around the world alone, of 1965, and Tania Aebi who embarked on the same venture at 18 years of age in May, 1985. Both achieved their goals and have excellent books (“Dove”, Graham), (“Maiden Voyage”, Abei) of their story.

I particularly was caught up in Robin’s voyage as I was a teen as well and was up dated frequently by National Geographic Magazine who covered the story. He was sixteen when he headed west from Southern California in his 24-foot sloop called Dove. Unlike the record breaking non stop teen sailors of today, Robin was out to sea for 1738 days. He stopped to explore, repair; took his time. He met the woman he would marry and did so along the way.

Tanei, on the other hand, left from New York City Harbor heading towards Bermuda. She had hardly any sailing or navigation experience and was not properly prepared for the voyage, but through her determination and common sense, she sailed back into New York City over 2 years later. I have met Tanei a number of times a various boat shows where she and I both had booths selling our wares: her book and my Learn To Sail cdrom.

The recent press of the search and rescue of Abby Sunderland has brought critics out of the woodwork creating a controversy of the safety of teen world solo sailing. They question the parents’ responsiblity and judgement in letting them go, some even to the extent of questioning wheather they love the kid or notoriety more!

Are they forgetting about Robin Lee Graham who was just 16 when he set sail?

And how about Tania Aebi, who with little experience, no GPS (same with Graham) and a boat that had factory defects that could have put her in treacherous situations?

Right now Abby Sunderland, sure defends her right to sail at a young age. After all, her brother successfully did!

From her blog:

“There are plenty of things people can think of to blame for my situation; my age, the time of year and many more. The truth is, I was in a storm and you don’t sail through the Indian Ocean without getting in at least one storm. It wasn’t the time of year it was just a Southern Ocean storm. Storms are part of the deal when you set out to sail around the world.”

Looking around I found that Robin Lee Graham, was the 1st recorded to set out..following:

Tania Aebi, Age 18, Completion: 892 Days

Brian Caldwell, Hawaii, US, Age 19 Completion: 477 Days,

David Dicks, Australia, Age 17 Completion: 265 Days

Jesse Martin, Australia, Age 17 Completion: 327 Days

Zac Sunderland (Abby’s Brother), California, US, Age 17 Completion: 327 Days

Michael Perham, England, Age 16 Completion: 284 Days

Jessica Watson, Australia, Age 16 Completion: 210 Days

The young will keep sailing!